s students gathered at campuses around the country, some schools were forced to close down in-person instruction just days into the fall term. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to force educators to rethink syllabi, including how to use remote teaching tools and software to provide students with a fulfilling experience. Educators are adjusting, postponing or attempting to combine remote methods and in-person instruction for skills that cannot be learned over a screen and a WiFi connection.

When the virus first struck, many workplaces and schools shifted to remote work/instruction. Some faculty at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, used Zoom or Google Hangouts applications to conduct classes and communicate but that option did not always prove accommodating to all students.

“I personally tried not to teach with a Zoom meeting,” says Mark Prosser, assistant professor in Ferris State’s welding engineering technology department. “Our campus is in a rural setting and some students live in areas where internet is not always reliable.”

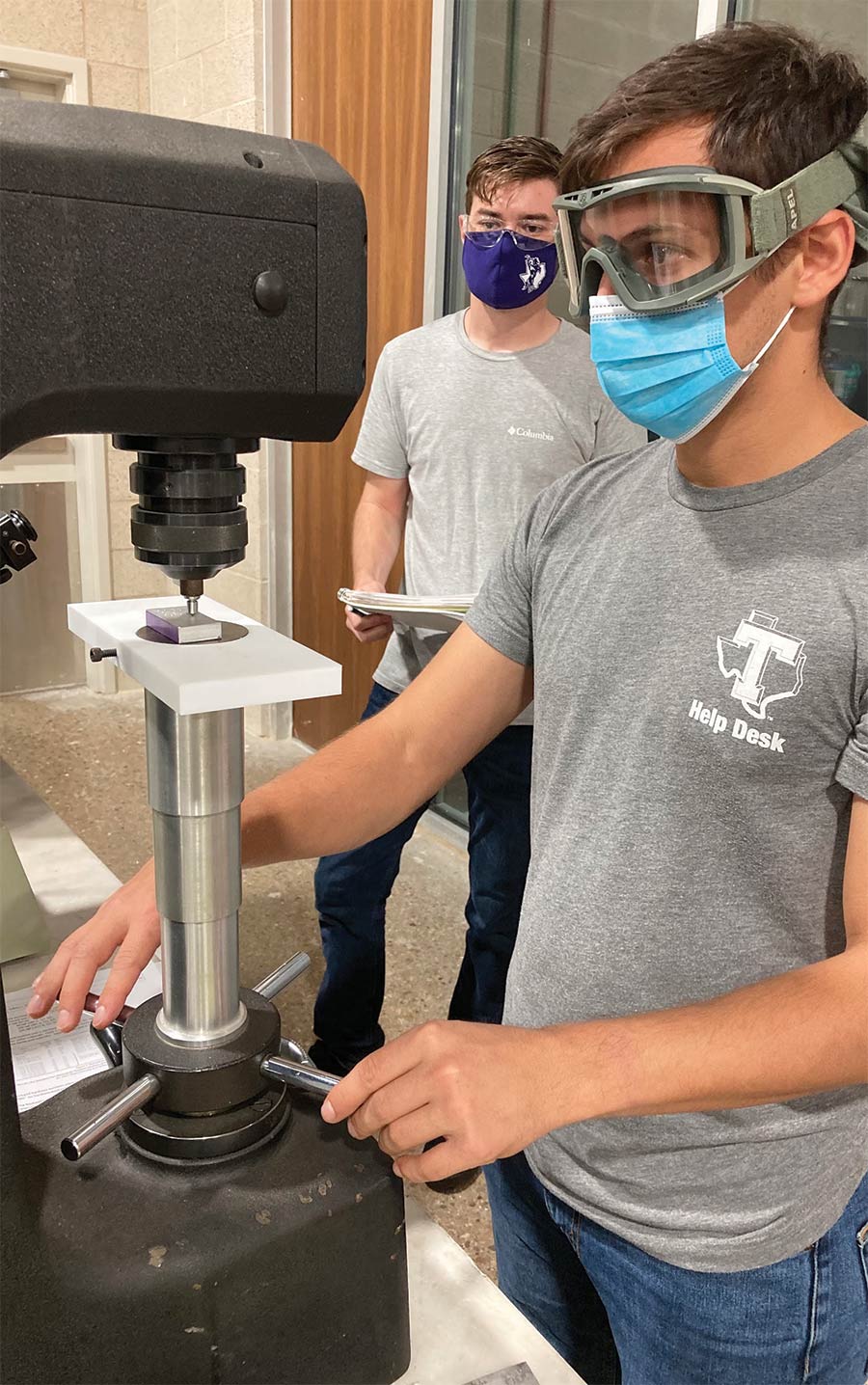

“Some components of this can be taught online but it all starts with hands-on skills,” Prosser explains. “Developing the necessary eye-hand coordination, muscle memory and the physical attributes necessary to make a competent weld can only be done in a lab. It’s no different from learning to shoot a basketball or swing a golf club. There is no way to develop that skill without doing it.”

“This fall, we’re offering online classes for our most basic courses like intro to welding, metallurgy; courses that build the foundation of knowledge but come before the more advanced welding classes,” says Jose Bueno, adjunct welding professor at American River College in Sacramento, California.

“Metalworking along with welding require two different components: theory and skill,” Prosser says. “These cannot be grouped as one thing. One cannot take the place of the other and one is not more important than the other. The two subjects work together.”

We invite students to post questions so it’s not only the instructors talking.

We invite students to post questions so it’s not only the instructors talking.

“The catch to video presentations,” Prosser continues, “is that training videos are challenging to produce and require practice. Anyone can make a video presenting a concept, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be any good. Videos can be very effective if done correctly.”

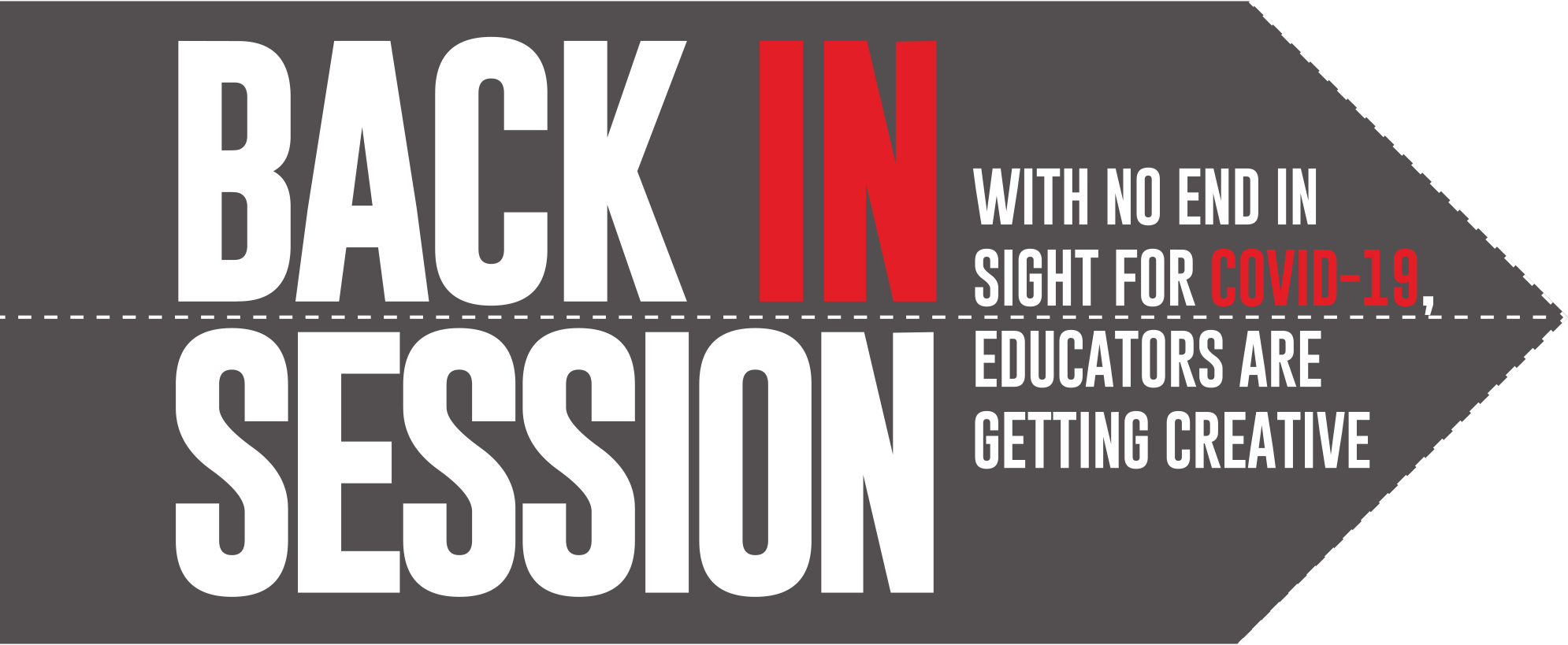

“I wanted students to have a bit more knowledge and experience about what they’re looking for, about what a weld looks like under the hood,” Bueno says. “We made some of our own demos and created a YouTube channel so students can build their familiarization with what a weld even looks like because they won’t be able to see it in person at first. Things like flaws, [close-ups of] porosity, cracks, etc.”

Last summer, instructors worked on transitioning lessons into video or other forms of online communication in preparation for the fall session. “We just expanded our licensing to be able to use Hobart demonstration videos, for example,” American River’s Bueno says. “We’ve had to get creative. We’re planning on extra quizzes and online discussion boards, inviting students to post questions on any topic we’re covering. That way it’s not only the instructors talking.”

“Online forums among students have sparked some good discussion,” Bueno says. “And students who might not feel comfortable raising their hand in an in-person classroom setting are able to contribute.”

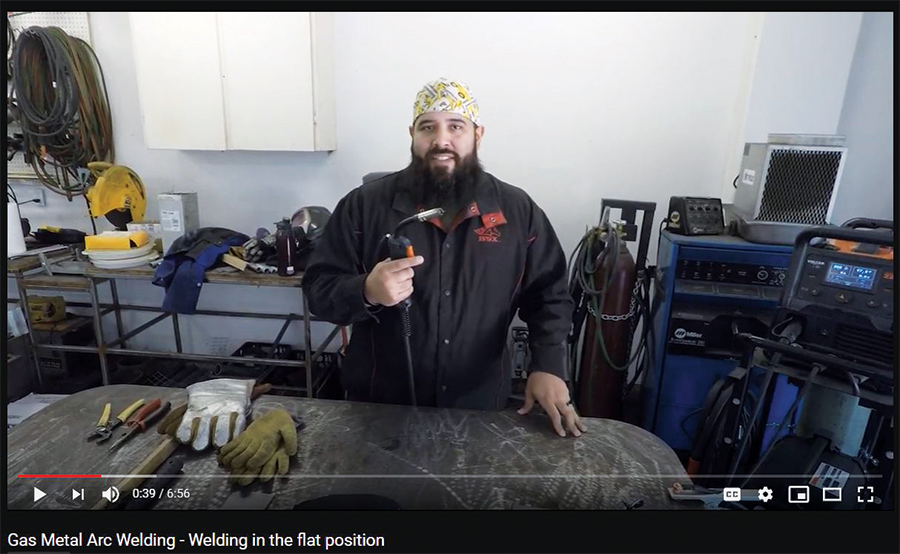

At Hill College in Hillsboro, Texas, classes are set up as a hybrid mode of in-person lab work instruction and online textbook assignments. “We are observing CDC health practices such as checking for fever or other symptoms and asking about any possible exposure to COVID-19,” says Joe Price, welding coordinator and instructor. Students are required to wear masks and clean machines after each use.

Hill hasn’t used Zoom or Google meetings to conduct lessons. “I look for good feedback after explaining a topic, like clear responses. It’s more difficult to get all of this feedback online and takes more time when using an online platform,” he says.

Hands-on and lab-based classes are being held on the Green Bay, Wisconsin, campus of Northeast Wisconsin Technical College this fall. “It’s impossible to learn how to weld simply from watching a video,” says Jeff Rafn, PhD, president of NWTC. The lecture portion of instruction will be delivered through web conferencing.

“Fortunately, the college had the last eight weeks of the spring semester to try new approaches and a summer to develop and refine the selected learning delivery strategies for fall courses,” Rafn says.

NWTC worked to reduce class sizes to mitigate COVID-19 exposure. “We need to reduce the student density at any one time on the campus,” Rafn says. “The challenge is maximizing remote learning while maintaining the essence of a technical college—which is hands-on learning.”

Tulsa Welding School in Oklahoma emphasizes learning by experience but is limiting in-person campus instruction. TWS created online courses that include the same information that would be learned in the classroom.

“The in-person component is key for every student to excel in the workplace post-graduation, so we needed to ensure we could still provide hands-on lab time but minimize the in-person classroom portion of training,” says Chris Schuler, director of training.

Across its three locations, TWS is using YouTube training videos as well as BlueJeans video conferencing for virtual face-to-face instruction.

Skills can be shown virtually but until the student physically attempts it, we cannot truly evaluate them.

Skills can be shown virtually but until the student physically attempts it, we cannot truly evaluate them.

Instructional videos are good supplements, but hands-on training is key for many fabrication processes in order for students to gain confidence in their abilities. “Our didactic curriculum lent itself best for virtual training, combined with online access to instructors for interactive instruction,” Schuler says.

Subjects of interest include automation integration into traditional fabrication methods, CNC plasma cutting, waterjet cutting, robotic welding and programmable bending machines. Class sizes have been reduced.

Ferris State’s Prosser says students are signing up for fabrication courses with the desire to build. Instruction covers numerous areas requiring in-person instruction, including heavy plate, tubing, thin-gauge sheet and various alloys.

“This is why skilled trades have been neglected for so long,” Prosser says. “Someone thought theory could somehow take the place of skill and it just can’t. A competent welding engineer or fabricator must possess both of these very valuable attributes.”

“If there is high demand, a person can go to work as a helper or as an entry-level worker and earn a decent wage while learning some skills,” Price says. “When the economy slows down, I get some of these individuals to come back to the classroom to increase their skill level so they can move on to a better position.”

The majority of students want to weld on pipelines, power plants or new construction. “Our students go on to the local fabrication businesses as well,” Price says. “We are fortunate to have a diverse and active local industry.”

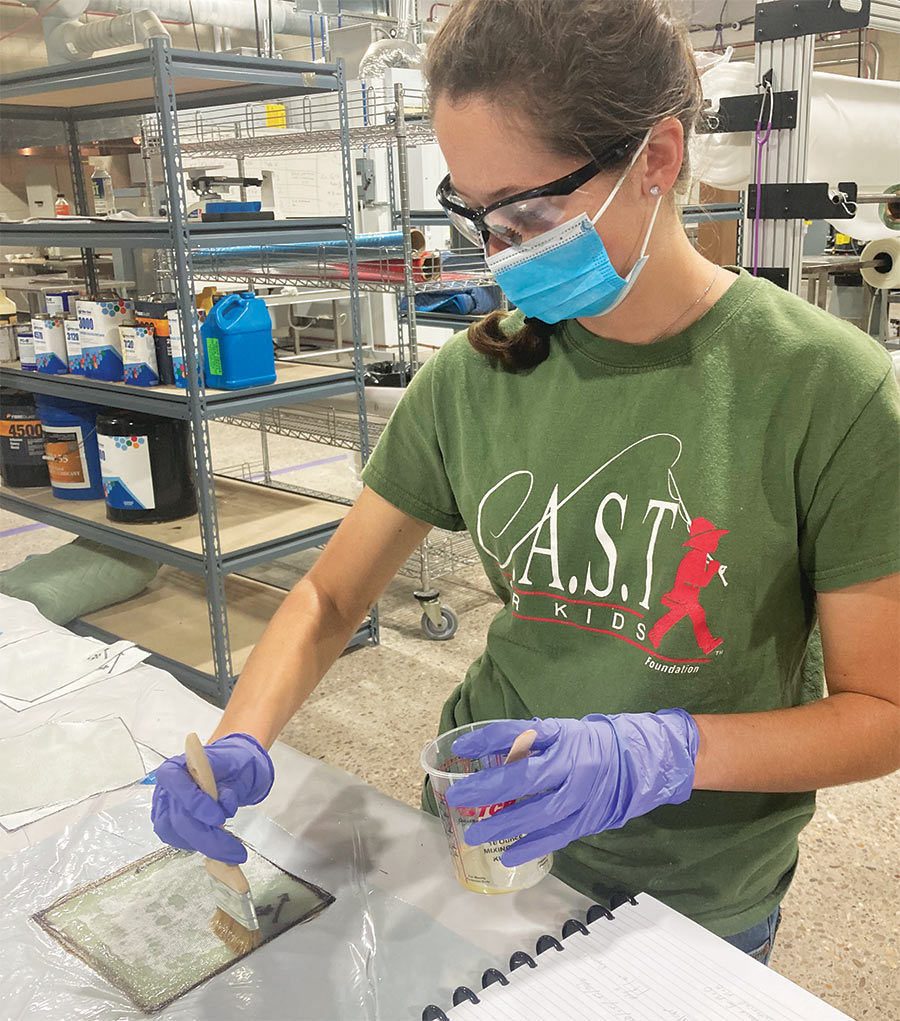

“It’s learning the little—but important—things, like how to use a grinder, read a tape measure, when and how to use eye protection and a face shield because you never know what may pop up under your safety glasses,” Bueno says.

It’s difficult to get feedback and takes more time using an online platform.

It’s difficult to get feedback and takes more time using an online platform.

Each passing month brings with it the continued evolution of off-campus and hands-on instruction, including lending equipment and offering WiFi hot spots as needed. “For those without access to broadband, the college is establishing access through its five remote learning centers,” Rafn says.

Employers increasingly seek a broad skill set in their workers. “Providing students with knowledge and experience in several aspects of the fabrication arts has proven to be effective; our students are securing employment prior to graduation,” Rickerson says.

HPA also provides value added services such as tight tolerance waterjet cutting, shearing, grinding, marking, and many other services.

HPA’s friendly and knowledgeable staff is always waiting to help you with your alloy needs.

HPA’s friendly and knowledgeable staff is always waiting to help you with your alloy needs.

HPA is ISO 9001:2015 Registered and DFARS compliant.

HPA’s friendly and knowledgeable staff is always waiting to help you with your alloy needs.

HPA’s friendly and knowledgeable staff is always waiting to help you with your alloy needs.

HPA is ISO 9001:2015 Registered and DFARS compliant.

The main goal for Price is to continue working with students in the lab at Hill College. “We are following the recommended COVID-19 practices to keep everyone safe,” he says. “I talk about good hygiene on the job site. A worker can be exposed to unhealthy conditions very easily. Teaching good habits becomes part of their safe mindset.”

We need to design new ways to deliver hands-on experiences in virtual environments.

We need to design new ways to deliver hands-on experiences in virtual environments.

Institutions that have put in-person instruction on hold are waiting to see if infection rates decline to allow for regular teaching sessions in spring 2021 (which begin in January). “We are riding the wave to see whether we open back up or not,” Bueno says. “Initially we were planning on hybrid classes until new guidance came down and we shifted to remote classes. We’re pretty optimistic and hoping for a better situation in the spring.”

Throughout the pandemic, TWS has continued to help graduates find jobs. Students are prepared to work within the industry as well as comply when additional skills testing is required. “That shows us that employers not only trust the training but also have a continued demand for skilled workers,” Schuler says. “Employers primarily need entry-level welders who can perform to certain standards and are willing to adapt.”