n 1850, Isaac Singer invented an affordable sewing machine that could push thread through fabric at 800 stitches per minute. In 1873, he bought 32 acres in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and built the Singer Sewing Machine Manufacturing Co. The main assembly building was almost half a mile long. A forge, foundry and 6-mile-long railroad completed construction of the complex. Singer quickly grew to a workforce of 6,000 and its factory floor space soon expanded by nearly 100 acres. At the turn of the century, the brand introduced the first practical electric sewing machine. Other improvements followed. In 1941, with America poised to enter WWII, employment at Singer had reached nearly 10,000 people.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, demand for Singer products declined in the face of strong competition from lower priced imports. By 1980, the employee roster had dwindled to 2,300 employees. Singer closed the Elizabeth plant permanently in 1982. Other factories and plants followed, leaving Elizabeth a shell of the thriving industrial community it once was.

Moser, who retired from GF Machining Solutions where he served as president and chairman emeritus for 25 years, established the nonprofit Reshoring Initiative in 2010. “I had an epiphany,” he says. “About 20 years ago, I drove past the old Singer building, which still stands at First and Trumbull streets. Nothing exists of the business that was once so robust. I have since seen company after company destroyed by imports and thought, ‘someone needs to turn this around.’”

The Reshoring Initiative provides the data and tools manufacturers need to demonstrate that, in many cases, local production can reduce total cost of ownership for purchased parts and tooling. Participating suppliers also are trained on how to effectively use these devices to sell against lower priced offshore competitors.

In addition to manufacturers, the Initiative makes versions of the ISP program available to economic development organizations, trade associations and technology suppliers through its Manufacturing Extension Partnerships (MEP). Moser’s organization uses its Supply Chain Gap program (SCG) to help companies identify products they could make to fill national supply chain gaps.

We’re always looking for companies, MEPs and economic developers we can assist to drive reshoring.

We’re always looking for companies, MEPs and economic developers we can assist to drive reshoring.

Harry Moser,

Reshoring Initiative

We’re always looking for companies, MEPs and economic developers we can assist to drive reshoring.

We’re always looking for companies, MEPs and economic developers we can assist to drive reshoring.

Harry Moser,

Reshoring Initiative

We’re always looking for companies, MEPs and economic developers we can assist to drive reshoring.

We’re always looking for companies, MEPs and economic developers we can assist to drive reshoring.

Harry Moser,

Reshoring Initiative

Mary Miller, business development lead for the University of Dayton Research Institute (UDRI)’s FastLane Manufacturing Extension Partnership program, says that helping local manufacturers leverage their equipment and skill sets to make personal protective equipment (PPE) during the pandemic led her group to take a closer look at reshoring. “The shortage of personal protective equipment early on in the pandemic showed us how vulnerable our supply chain is,” she says. “But, it also opened our eyes to opportunities.”

FastLane coordinated face shield PPE production by working with Ohio companies to produce tools and molding while assisting other companies to ramp up mass production of face shields. The West Central Ohio MEP also helped Piqua, Ohio-based Industry Products Co. pivot from manufacturing automotive parts to making hospital gowns.

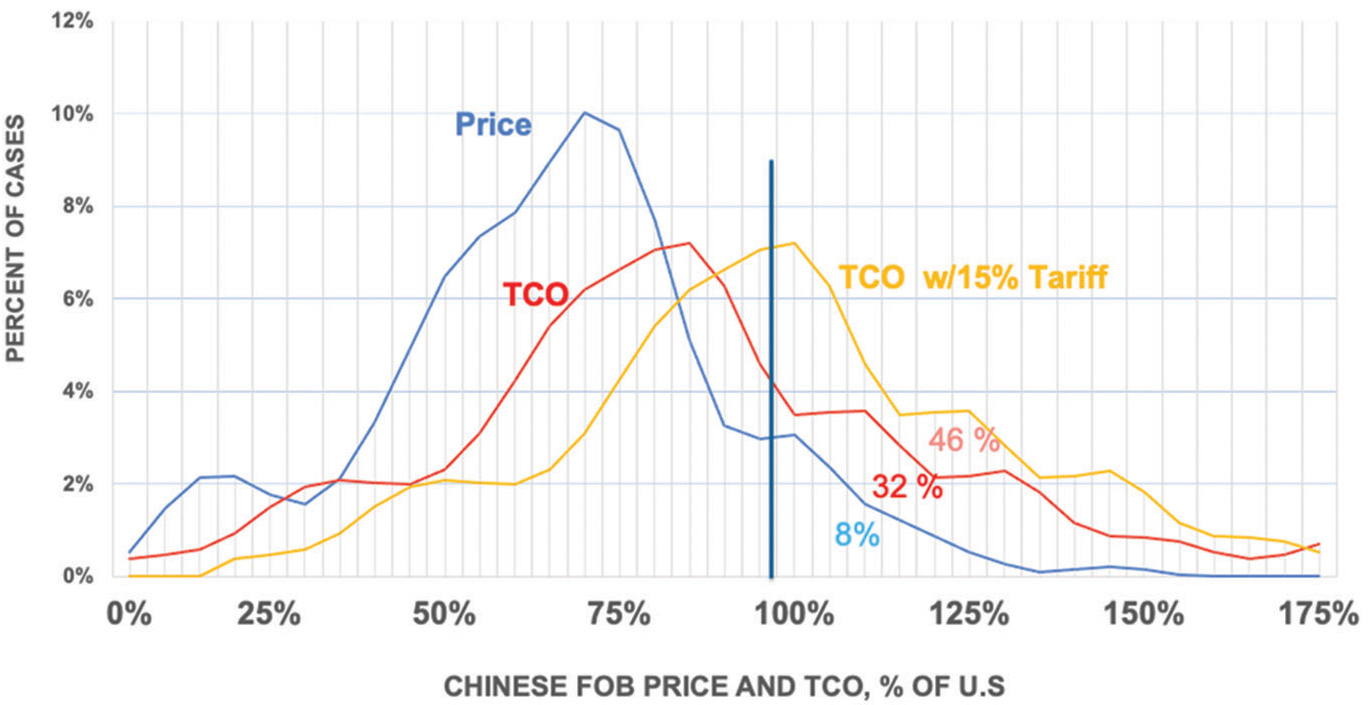

“The PPE situation demonstrated to us that manufacturing parts and products in the U.S. isn’t as expensive as everyone thinks it is,” says Miller. “I think part of the problem for a lot of buyers is that they tend to focus on what is right in front of them. It takes more effort to consider an option like reshoring because you have to take into account things like total cost of ownership, which includes tangibles such as tariffs, shipping and inventory costs as well as intangible elements like time zone differences and language barriers.”

According to Miller, training is a crucial step for both manufacturers and their suppliers. “Harry educates and trains people with tools like his Total Cost of Ownership Estimator,” she continues. “Partnering with Harry and taking advantage of his program’s resources to help Ohio manufacturers be more competitive was a great marriage for us.”

“We’re at the front end of the process,” Miller says. “Harry’s kind of the man behind the curtain. We provide value in several ways. If the data Harry generates from the initial discovery process reveals that a company needs to reduce the cost of its products, we can help with that either by weeding out unnecessary processes or by helping them add technology that boosts efficiency.”

FastLane targets small to medium-sized manufacturers and already has a couple companies interested in reshoring. “We’re trying to educate prospective clients about how to navigate total cost of ownership and understand the value of what they have to offer so that they have a fighting chance with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) when they go toe to toe with an overseas competitor,” Miller says. “If OEMs are interested in reshoring, now is the time to look at their supply chains and evaluate the risks associated with them. Now is the perfect window for this opportunity.”

The Illinois Manufacturing Excellence Center (IMEC) is also an MEP participant with the Reshoring Initiative. The organization has a track record of assisting more than 700 companies a year with successful improvement and innovation projects.

IMEC contracted with the Reshoring Initiative in August 2020, targeting small to medium-sized manufacturers. According to Boulay, smaller companies tend to look at reshoring as an opportunity to grow their business by opening the door for more local sourcing. Leadership can serve as a tell, identifying companies ripe for the program.

“Leadership is a willingness to look at opportunities wherever they might be,” he says. “It also means being open to exploring avenues that might lead to a different way of capturing business. Once they sign up for the Reshoring Initiative’s program through us, Harry’s team uses its data to help identify imports that might be a match for products they make, the potential scale-up and who is importing. The program can help them get into a new supply chain.”

According to Boulay, IMEC currently has 36 companies in the Reshoring Initiative pipeline, with approximately 450 companies that are “kicking the tires.”

“We’re pleased with the uptick we are seeing,” he says. “The companies that have enrolled are business owners trying to make decisions about how to shape their company’s future. They’ve been pleased with the output they have received. It’s our responsibility to help manufacturers be globally competitive. Supply chains are a means to an end to serve our customers. We’re poised for our first success story where one of these companies completes the process and moves into a new supply chain to reshore a product.”

“We got our start here in the U.S. and we’re still making our products here,” says Joe Goral, director of sales and marketing for Bourn & Koch. “One of our founders, Loyd Koch, is still directly involved with many projects on our shop floor, including rebuilding and running machine tools.”

A member of IMEC, the machine tool builder has seen firsthand the ebb and flow of its industry. “Imports have certainly helped to contribute to the downfall of American machine tool companies,” Goral says. “Twenty-eight different machine tool companies that we now own were once prominent in the U.S., but now no longer exist. There are very few left. The vast majority of these shops live only on the pages of schematics and drawings. We still make parts and provide service for many of those products.”

Larry Bourn and Loyd Koch got their start in 1975 as a small machine tool rebuilder with a focus on specialty equipment, remanufacturing and retrofitting. From 1984 to 2016, the company grew through acquisition and expansion. Today Bourn & Koch focuses on new machine tools for gear manufacturing and precision grinding. The company has also continued to update technology for a select few of the machine tools lines it owns; namely Barber-Colman (Bourn & Koch), Blanchard, Fellows, and Springfield. Their latest machine, the MT3, is a multifunctional machine tool platform designed to be a value-engineered vertical ID/OD grinder that can be expanded to allow for vertical milling and turning all on one machine.

The company joined the Reshoring Initiative’s ISP program through IMEC. The data generated by Bourn & Koch’s in-depth company profile was revealing.

“The new data showed conclusively what’s coming into the country that we are already marketing and selling,” says Goral. “We took a deeper dive to glean some good action items our team could move forward with.”

Bourn & Koch discovered that its two primary customers were not purchasing foreign machine tools; that knowledge affirmed the company wasn’t losing market shares. Imports for competitive grinding machines were almost nonexistent. Data on gear manufacturing machines told a different story.

“We found there were a lot of gear manufacturing machines being imported, making this market pretty competitive,” says Goral.

Bourn & Koch is introducing a new precision vertical grinder this year. The machine can also mill and turn parts, reducing work-in-process time. Fabricators and job shops will be able to load the machine with a metal blank and take out a finished product. The new grinder will target the multifunctional machine tool market.

We got our start here in the U.S. and we’re still making our products here.

We got our start here in the U.S. and we’re still making our products here.

Working with IMEC has delivered other benefits to Bourn & Koch. “Our work with them has helped us identify skills gaps and how we can fill them,” he says. Bourn & Koch has also partnered with IMEC to provide training to staff members and is currently working on an augmented reality project for future training in building its machines.

The company is looking at the Initiative’s TCO Estimator as a next step. “We’ve always been a solutions-based company,” he says. “One of the things that makes us different from those we compete against is that we believe it’s not always about technology. Many times it’s about listening to customers and providing the right solution for their application.”

Goral adds that there is also a difference between importing and assembling machine tools in the U.S. and designing, engineering and building American-made tools. And there’s another intangible. “I was talking with an individual who said, ‘My machine tool fought Hitler.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘My machine tool was built during World War II and it fought Hitler.’ That feeling of pride people have in their equipment really stuck with me. For many, it’s not just a tool, it’s a legacy. One we want to continue to contribute to.”

“We track reshoring plus greenfield or incremental foreign direct investments,” says Moser. “Combined manufacturing job announcements grew steadily from 6,000 per year in 2010 to 190,000 in 2017, driven by Trump reductions in corporate income tax rates and regulations, but fell to 120,000 in 2019 primarily due to the trade war.”

Unable to forecast how tariff rates would affect products, many companies delayed decisions about production and capital equipment expenditures. In contrast, funds for reshoring were included in Trump’s CARES Act. “We are working with MEPs in Illinois, New York State, Ohio and Rhode Island to help suppliers find and win opportunities and convince OEMs to reshore and participate in local sourcing,” says Moser. “And we’re always looking for new MEPs, economic developers and companies we can assist.”

In 2020, reshoring exceeded FDI in job creation. Biden is proposing a 10 percent Made In America tax credit and a 10 percent surtax on offshoring. These would certainly help reshoring.” Extended members of the Biden policy team have also reached out to Moser for suggestions.

“If we look at the overall trends, we’ve been bringing in an average of 150,000 jobs a year, but that’s just enough to balance job loss due to automation and offshoring,” he continues. “We’ve been keeping our heads above water but we need to bump that number to 300,000 jobs per year. If we want to do that for the next 20 years, we need the capacity to do it. It will only happen if people use the TCO Estimator and the government further reduces the value of the dollar by about another 20 percent. The corporate tax rate needs to be kept low as well. We also need to shift our emphasis from liberal arts university degrees to apprentice programs because we need a lot more skilled professionals like precision machinists, toolmakers and welders.”