n his 1948 speech to the House of Commons, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” More than 70 years later, the iconic phrase raises an important question for service centers and manufacturers impacted by supply chain shortages. The black swan event that stretched around the world has exposed the frailty of the system, leaving U.S. businesses scrambling to gain a foothold in a volatile economy. Chicago Tube & Iron Co. Chairman Dr. Donald McNeeley, Ken Kaufmann Jr., president of CEP Technologies Inc., and Scott Schrinner, head engineer for a large HVAC manufacturer, talk frankly about the pitfalls and some of the steps they have taken to navigate the day-to-day challenges.

Chicago Tube & Iron Co. was founded in 1914 on Chicago’s South Side. The company has posted 107 years of consecutive profitability—a feat that has provided it with the capital for continued growth and job creation. Today, the service center, along with parent company Olympic Steel Inc., has 34 locations throughout the U.S. and Mexico with 4.2 million sq. ft. of processing facilities. Chicago Tube & Iron ranks among the top 10 distributors in the U.S. for round mechanical tubing; aluminum pipe, tube and bar; carbon steel pipe; cold finished/hot roll bar and ASME pressure parts.

“We have inventory shortages from ketchup packets and pickles to semiconductors and nearly everything in between,” he says. “The chokehold on semiconductors alone has resulted in record shortfalls for new and used cars and rentals. Our over-reliance on imports from China and labor shortages created because employers can’t compete with inflated unemployment benefits add to the problem.

The pandemic has revealed that the system is brittle and leaves us vulnerable to black swan events.

The pandemic has revealed that the system is brittle and leaves us vulnerable to black swan events.

Typically an oversupply of goods or services reduces prices, resulting in higher demand. Conversely, an undersupply results in higher prices and lower demand. Equilibrium is achieved when supply and demand balance each other and prices stabilize.

With more than 40 years at the helm of Chicago Tube & Iron, McNeeley has seen his share of volatility. “COVID-19 created an 18-month shutdown,” he says. “Demand fell significantly. As a result—at least temporarily—we had surplus inventories in the supply chain. In 2021, demand came back with a vengeance. When the doors opened, demand grew exponentially and surplus inventories in the channel were quickly depleted.”

These deficits affected lead times. According to Deloitte’s 2021 Manufacturing Industry Outlook, a survey revealed that only 21 percent of respondents had confidence in their supply network’s visibility and capacity to quickly “flex sourcing, manufacturing and distribution, if needed.” National consulting firm WestMonroe conducted an executive poll that found a majority of organizations conceded they will likely still be recovering during early 2022.

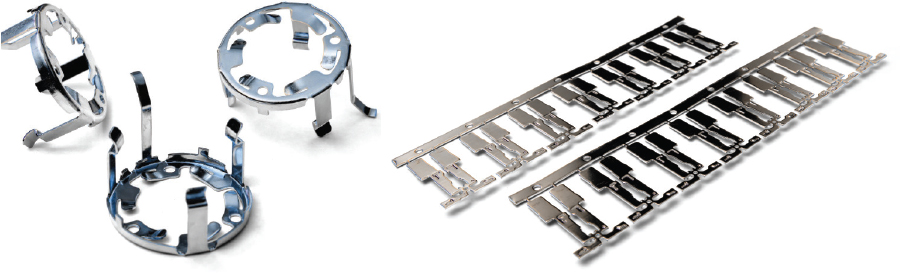

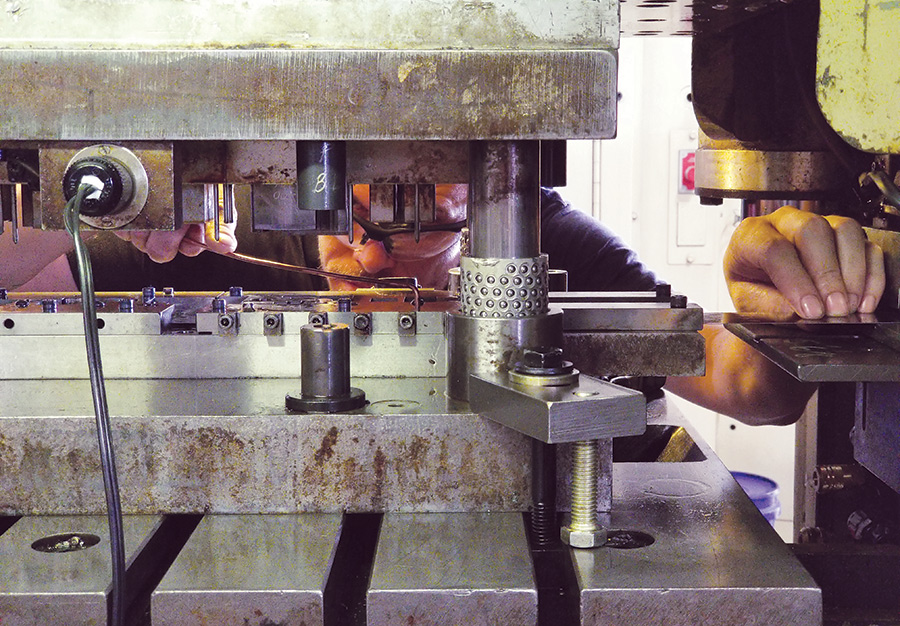

The stamper can maintain a profile tolerance of 0.0015 in., a maximum part burr size of 0.0005 in. and flatness tolerances of less than 0.003 in. Headquartered in Yonkers, New York, CEP’s production facilities in San Antonio, Texas, and Chengdu, China, can support medium- to high-volume production runs ranging from 25,000 pieces to 100 million pieces a year. Its presses, ranging from 15 to 60 tons, can run material as thin as 0.002 in. to 0.125 in. The company also provides rapid prototyping, reel-to-reel and barrel plating, heat treating, deburring, anodizing, e-coating, cleaning and tape and reel packaging.

For certain industries, there may only be one or two suppliers you can go to for the product you need.

For certain industries, there may only be one or two suppliers you can go to for the product you need.

“Let’s say I have a job that calls for 100,000 pieces a month but I’m delayed a month or more because of raw material shortfalls,” Kaufmann says. “Material tends to come in all at once, which means I have to double and triple my capacity to catch up. Then I have to send all those parts to my supplier for heat treating, plating and other processes to clear my backlog. That means they are inundated. It’s the proverbial domino effect.”

Kaufmann notes that CEP’s China facility is not experiencing the supply chain delays in metals that the U.S. is seeing. China’s tendency to hold inventory versus America’s just-in-time manufacturing practices could explain that difference. In general, though, “multiple locations don’t matter for manufacturers at the high end of the supply chain,” he continues. “When you are at our level, there are not many suppliers you can turn to. Manufacturing in the U.S. has been in a consolidation mode for a number of years. That condition was compounded by the pandemic. For certain industries, there may only be one or two suppliers you can go to for the product you need.”

Steel, copper and other metals are at record highs—the highest in the industry’s history.

Steel, copper and other metals are at record highs—the highest in the industry’s history.

At his day job, “we began to experience some major supply chain bumps eight months ago, primarily with variable frequency drive (VFD) electrical components and programmable logic controls (PLC),” says Schrinner. “These parts all need semiconductors. Now we’re having difficulty sourcing standard hardware like aluminum pipe fittings. It’s a very common product but it carries a six-month lead time.”

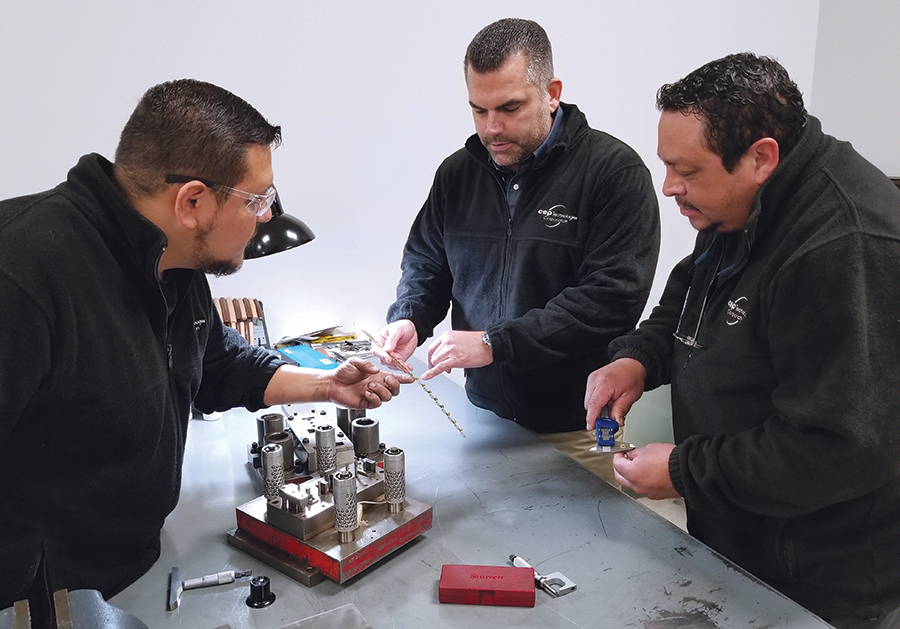

Ray Ramos, left, CEP President Ken Kaufmann Jr. and Roy Rincon discuss a tooling issue.

“We are at pre-COVID production levels with pre-pandemic lead times, but we have to work harder to get material and components to meet required timeframes,” Schrinner says.

Working harder means fabricating parts, or purchasing near components and modifying them, in house. The company has had to buy parts at consumer list prices when they can’t be purchased through preferred vendors at OEM pricing.

“Our stainless sheet has to be shipped expedited freight so we can meet deadlines,” Schrinner says. “Our copper tubing supplier isn’t taking orders in 2022 because of the backlog. We placed an order in February and received it in May. We placed another order in April, and it’s not scheduled to arrive until February 2022.”

Our copper tubing supplier isn’t taking orders in 2022 because of the backlog.

Our copper tubing supplier isn’t taking orders in 2022 because of the backlog.

That isn’t as easy. The requirement for UL-certified parts restricts the number of alternate components Schrinner can use. UL-listings ensure parts meet safety standards for operation. “If I can’t get a circuit breaker I need, I can’t just go out and buy one from another company because it may not be UL-listed,” he says. “If I can’t find a viable alternative, I have to go back to UL, report my findings and request that they approve the part and add it to our file for approved parts. That also usually means a hefty price tag. You don’t see these types of costs in normal manufacturing, but [such situations] will last as long as we’re dependent on other countries for raw materials and electrical components.”

A fix for the supply chain might mean accepting a bit less optimization—“one that allows for a buffer inventory that can help head off the negative impact of an event like this,” he says.

If there’s a silver lining to be had, McNeeley, Kaufmann and Schrinner agree there are answers to be found in transparent communication up and down the pipeline; partnering with customers and suppliers; reshoring and reconstituting education to preserve and grow the skills that form the backbone of U.S. manufacturing.

While the pandemic has exposed supply chain flaws and weaknesses—some of which have been brewing for years—it has brought many back to their roots. Inventiveness and the flexibility to consider doing things a different way has resurfaced.

“In Greek mythology, the phoenix was a bird that cyclically regenerates,” says McNeeley. “The industry will, too.”