earning through inquiry-based projects enables high school students at Science Leadership Academy (SLA) at City Center in Philadelphia to dig deep into the subject matter, says John Kamal, an engineering teacher at the school.

For example, instead of providing students the equation for how a pendulum moves, they create a pendulum, collect data, hypothesize about possible formulas that describe how a pendulum moves, debate the formulas and jointly reach a conclusion. “That’s how they learn the formula,” Kamal says. “That way, we believe students can understand the underlying principles of critical thinking and how science works.”

Fabricating projects in the engineering program’s shop helps prepare students for not only continuing their education after high school and, more importantly, for life. Kamal notes that students who are accepted into his program spend more than 1,000 hours studying engineering, including a lot of fabrication in class and as part of the after-school robotics club.

A capital grant presented the engineering program with the opportunity to add to the shop’s equipment list, so Kamal says the school decided to use the money to purchase an abrasive waterjet cutting machine. A waterjet’s capability would enable the shop to cut complex shapes in steel, such as for a protective plate for a robot, rather than outsourcing it to a machine shop with a waterjet.

Below: ProtoMAX waterjet machines being produced at Omax’s facility in Kent, Washington.

I put water and garnet in, and out come finished parts.

I put water and garnet in, and out come finished parts.

Kamal says he didn’t need to conduct an extensive amount of research and testing to determine that the ProtoMAX waterjet from OMAX Corp. in Kent, Washington, was the way to go. “Some of the mentors for our program and for our club had experience with this particular waterjet. They recommended it, and I quickly saw it as the most viable option, and it fit within the budget.”

The compact, self-contained OMAX cutting system has a 12-in. by 12-in. cutting envelope and is well-suited for prototyping and low-volume machining of almost any material up to about 1 in. thick. Being self-contained is critically important, Kamal says. “I put water and garnet in, and out come finished parts.”

A large waterjet for industrial applications would be more complex to operate and not suitable for the academy, according to Kamal. “You have to worry about what you will do with this massive sludge pile and taking up a much larger footprint, and I didn’t have those abilities here.”

At first glance, it’s not necessarily intuitive what Tiny WPA’s mission is. It’s an organization that co-founders Renee Schacht and Alex Gillian created to support and grow a multigenerational community of people “who want to learn how to design and build great things, make a difference in their communities, and, through design, lead others in Philadelphia to create safer, healthier, more prosperous and more equitable places to live, work and play,” explains Gillian, who also works as the organization’s director of design and learning.

Tiny WPA’s core activities include citizen-led public space and facility improvements; the creation of play spaces and the use of play to bring people together in new ways; and the Building Hero Project, a multigenerational community-design leadership and workforce development initiative that includes the Building Hero Training Program and Hero Fabrication.

“Creating further opportunities for Heroes to learn, earn and lead in the design and making of their city, Hero Fabrication ranges in scale from laser-cut [address] numbers for Habitat for Humanity to mobile playgrounds for Philadelphia Parks and Recreation,” says Gillian.

A reproduction of a Dox Thrash print, inserted into a frame that was cut on a ProtoMAX waterjet.

For one public space project, Tiny WPA partnered with Science Leadership Academy (SLA) at City Center in Philadelphia to use its waterjet to cut the frames that hold laser-cut reproductions of four prints by Philadelphia artist Dox Thrash. Dox, who lived from 1893 to 1965, served as a printmaker with the Roosevelt administration’s Works Progress Administration at the Fine Print Workshop in Philadelphia. Dox co-invented the carborundum mezzotint printmaking process.

One option for creating the frames was to cut steel parts and weld them together, but that would have consumed too much time and resulted in an inferior product, according to Gillian. Instead, Tiny WPA reached out to John Kamal at SLA to waterjet cut the frames on the school’s recently acquired ProtoMAX machine.

“We have a long-term relationship with SLA, where we helped them create their maker spaces,” Gilliam says. “We can’t possibly have every tool in our workshop, so we set up a distributed network of shops that have complementary tools so nobody has to have everything.”

Nonetheless, he says Tiny WPA is in the process of trying to find more space to expand its workshop and would eventually like to acquire a waterjet, albeit one bigger than the ProtoMAX. “In the larger scheme of things, getting a 4-ft. waterjet would be more practical for the projects we are doing in the near future and the social impact we expect to have through this pioneering work.”

Because the project will be on display outside of a library for two to three years, the corresponding stands had to be made of metal and the prints are fabricated from acrylic. Tiny WPA’s head of digital fabrication, Caprice Jackson, translated four of Dox Thrash’s prints into laser-cut reliefs. The carborundum mezzotint process enables a print to have fine gradients, Gilliam says, and the laser cutter that was used has limited tonal options, so Jackson had to decide which information to keep. “She had to make some difficult decisions, which would be challenging for any designer, much less a 20-year-old like Caprice,” Gillian says.

In addition to allowing passersby to feel their texture, he adds that they can make their own print by rubbing a crayon or pencil on a piece of paper placed on a laser-cut relief. “That’s pretty darn cool.”

The dimensions for the ProtoMAX waterjet are 39.5 in. by 56.6 in. by 41.5 in. Rather than place it in the shop, Kamal says he had the ProtoMAX waterjet installed in the classroom where he teaches. “It can just sit in the corner where the water and the power are. It sits perfectly fine in my classroom.”

To accommodate the waterjet, which has a traverse speed of 100 ipm and a linear positional accuracy of ±0.005 in., the school installed a new power outlet and voltage boosters to increase the school’s 208 volts to the 220 to 230 volts needed for the machine, Kamal says. Some plumbing work was also required. “It probably took a month to get it up and running.”

Allegheny Educational Systems Inc. in Tarentum, Pennsylvania, installed the waterjet, which required the better part of a day, Kamal says. “It’s a fairly elaborate setup and install procedure, but once it was done, I haven’t had to do any calibrating or fine-tuning or very much maintenance at all. It’s been fairly self-sufficient.”

Certain components, such as a 2-ft. by 3-ft. belly pan for a robot, are too large to fit into the waterjet’s cutting envelope and such parts would still need to be outsourced, but 90 percent of what the students need to cut on a waterjet fits within the ProtoMAX’s cutting envelope, Kamal says.

The waterjet, he admits, isn’t used extensively at SLA, but it proves its value when it is. One recent project that required waterjet cutting was done in partnership with Philadelphia-based Tiny WPA, which was named after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Work Progress Administration and supports community design improvement projects. The project involved creating frames for four reproduced prints by pioneering printmaker Dox Thrash. (See sidebar on page 47.)

“Each frame took about 45 minutes to an hour to cut,” Kamal says, noting that all the needed frames were cut in two days. With its 30,000-psi, direct-drive, 5-hp pump, “it’s not a fast machine.”

He notes that he appreciates that waterjet machining doesn’t create a heat-affected zone on the material surface, which is beneficial when producing a robotic gusset plate, for instance. “The last thing I want is to have a bearing hole with additional hardness or less tensile strength.”

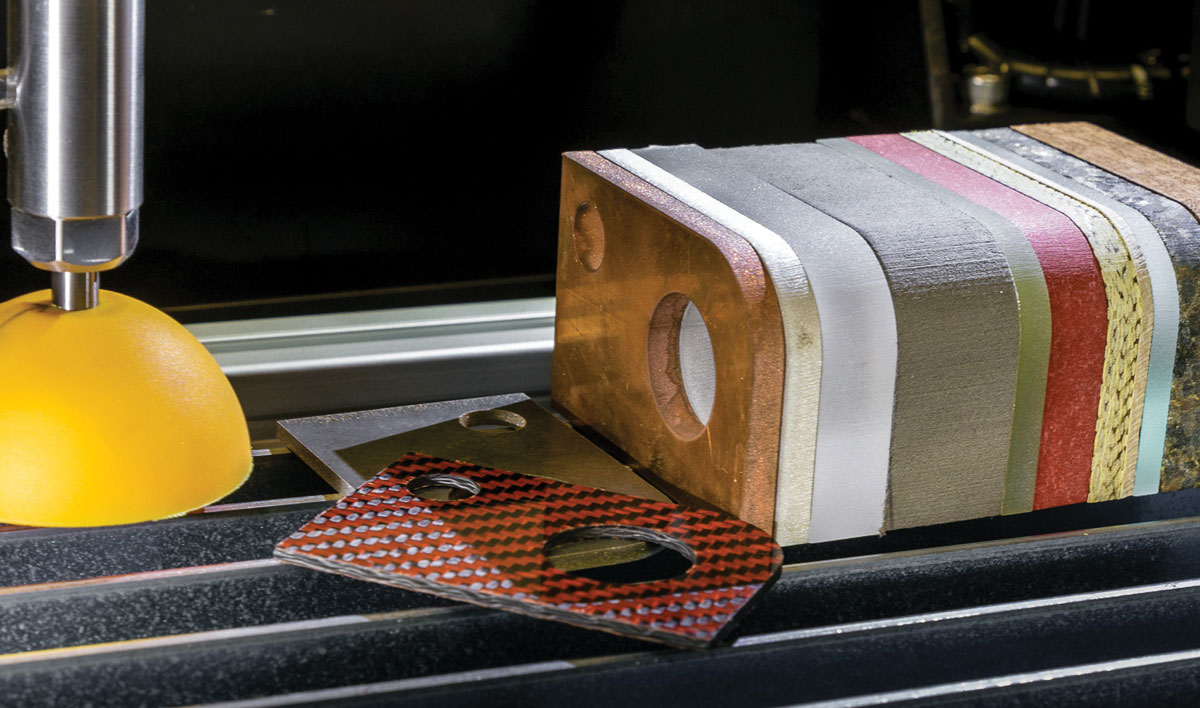

More importantly, the waterjet can cut more materials than the shop’s laser or CNC mills and lathes, Kamal says. The list of materials cut on the ProtoMAX so far includes aluminum, steel and slate, which barely scratches the range of suitable materials for waterjetting.

After cutting a part, the part edges have a matte finish and the corners are fairly sharp, so the cut surfaces are either ground, polished, buffed or finished in a vibratory tumbler.

The ProtoMAX comes with IntelliMAX software that offers features to ensure accuracy and optimize cut time, according to OMAX. “It’s got some quirks,” Kamal says, “but it’s generally pretty good.”

Overall, engineering program students have responded positively to the new piece of machining equipment, Kamal says. “It’s fun to watch and gives them a new range of abilities. They are excited about it.”