Once large volumes of blanks move downstream to forming operations, labor costs can become difficult to recoup.

upply chain disruptions, soaring raw material prices, transportation bottlenecks and war in Ukraine continue to make headlines. Making matters worse for fabricators is the massive labor shortage while manufacturing booms. By 2030, an estimated 2.1 million manufacturing jobs will remain unfilled, costing the U.S. economy up to $1 trillion. Retirements are outpacing replacements. Entry-level positions remain unfilled, and mid-level positions are left vacant as required skills become harder to find.

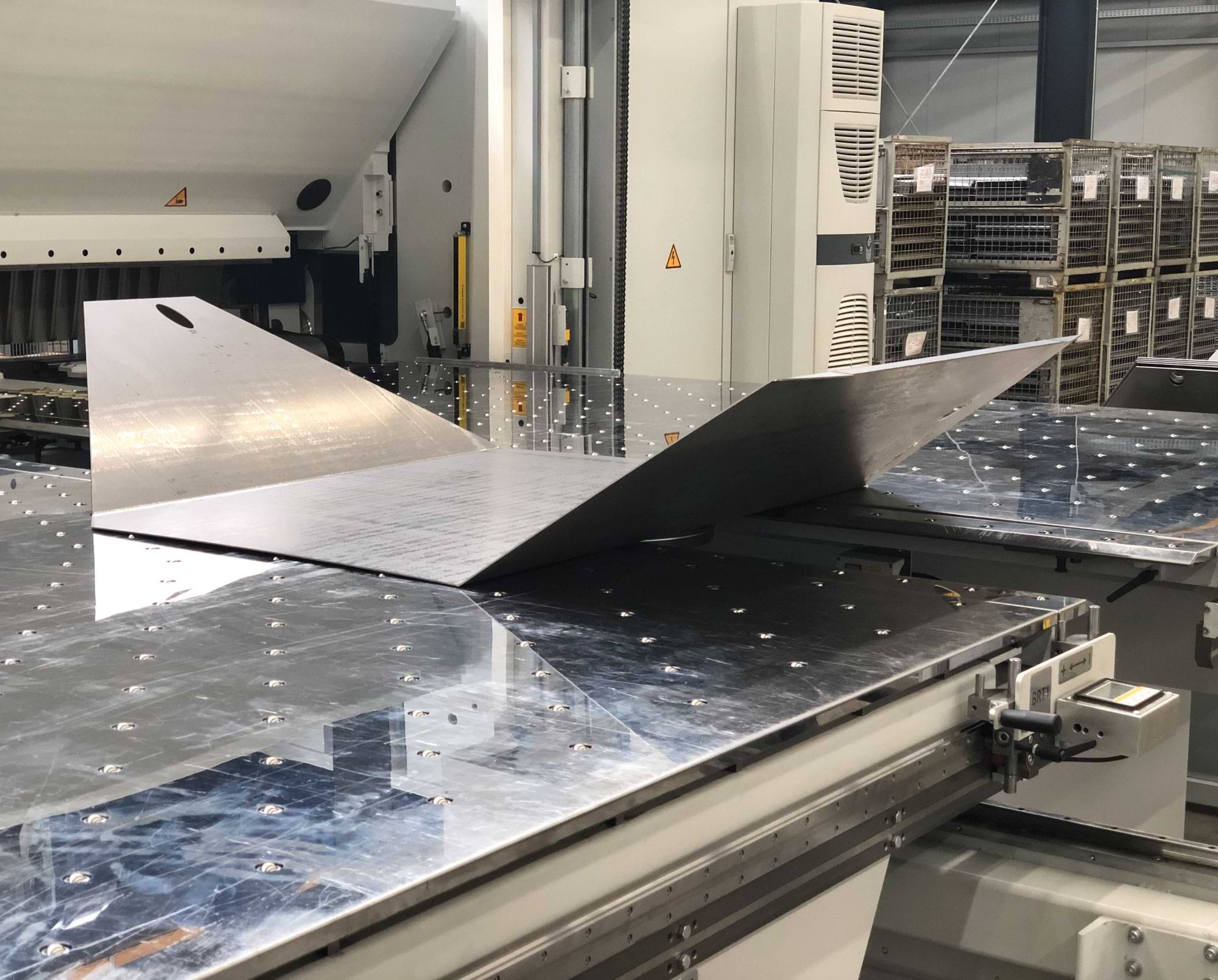

Identifying ways to attract a new workforce remain problematic for the industry. But technology solutions can help to curtail the need for labor while increasing output. For example, automated lasers, punches and combination machines have drastically reduced the need for operators and made it easy to produce large volumes of blanks. Once those blanks move downstream to forming operations, however, labor costs can become difficult to recoup.

Despite the advances in press brakes, forming is still a highly labor-intensive operation. Lifting, flipping and supporting parts, coping with the effects of material variations on accuracy, loading blanks and unloading finished product often require two or more operators.

Small robotic press brakes are often chosen for high-volume production of smaller profiles, while panel benders are typically used for mass production of thin-gauge panel-type profiles. But for those applications in between, metalformers are turning to the high-tech folder.

One operator on a single folder can easily replace the production value of multiple press brakes.

One operator on a single folder can easily replace the production value of multiple press brakes.

One operator on a single folder can easily replace the production value of multiple press brakes.

One operator on a single folder can easily replace the production value of multiple press brakes.

Folding eliminates two of the biggest issues press brake users struggle with. The ergonomics of handling parts, and material variation in thickness and tensile strength each have a huge impact on labor and are the primary reasons behind the enormous labor content of bending parts. Not so with a folder.

A blank is fed onto the folder’s gauge table and positioned against a reference stop. The vacuum gauge system grips the part, and from a single datum point automatically feeds it from one bend to the next. Bend-to-bend dimensions are accurately held regardless of part size. And one bend has no impact on the next.

The part is brought back to the operator when done, rotated to the next side, and the process continues. The part never leaves the horizontal plane. It is never lifted or flipped and is easily manipulated on a ball-transfer gauge table. One operator on a single folder can easily replace the production value of multiple press brakes.

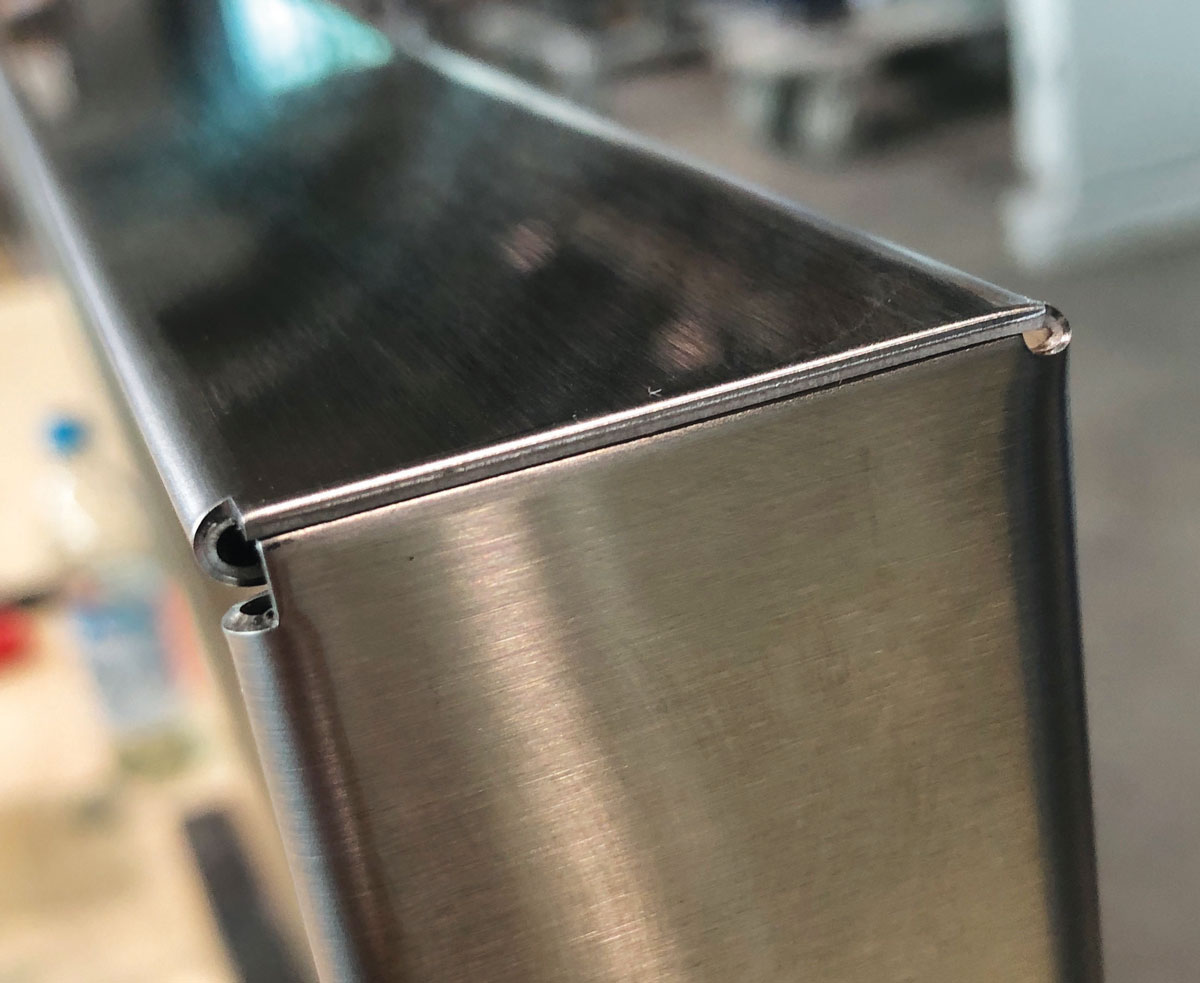

While material variation has a huge impact on the repeatability of parts formed with a press brake, a folder eliminates that problem. Unlike a punch and die, which uses both surfaces of the material, a folder bends using only the outside surface. The nominal variation in material thickness has little to no impact on the resulting angle.

Tensile variation has significantly less impact on folded parts as well. Springback is compensated for in the same manner, but the over-bend calculation holds true with little variation between parts. By removing material impact on part accuracy, a manufacturer obtains precise, repeatable parts that require little operator oversight.

Folding consistently accurate parts also supports downstream operations by contributing to improved part fit-up, faster assembly, less scrap and higher quality. Alternative methods can also be employed for further labor reductions. For example, consistent part fit-up makes robotic welding easier to employ. Depending on downstream processing, these savings can be the biggest source of a folder’s return on investment, sometimes larger than upstream savings.

The number of companies taking advantage of folding technology’s benefits is growing rapidly. Labor-intensive operations are no longer sustainable, making folders an attractive solution for manufacturers seeking low-labor alternatives to traditional bending methods.