t took 7.6 million lbs. of steel, 2,000 men and 2,200 days of on-site labor to complete the Golden Gate Bridge in 1937. A $25 million grant from President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program made construction possible for what is still considered an engineering marvel. Annual tolls and fees averaging $145 million help offset the Golden Gate’s yearly $85 million maintenance bill.

For state and local bridge owners across the nation, the weight of maintenance demands has grown increasingly burdensome. It’s a story The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has been telling since 1988 when it issued its first quadrennial Infrastructure Report Card. The nation’s latest marks, posted in 2021, tallied a C-. The bridge category scored a C. The U.S. has a total of 617,000 bridges. According to ASCE, 42 percent of those bridges are at least 50 years old, with 46,154 flagged as structurally deficient.

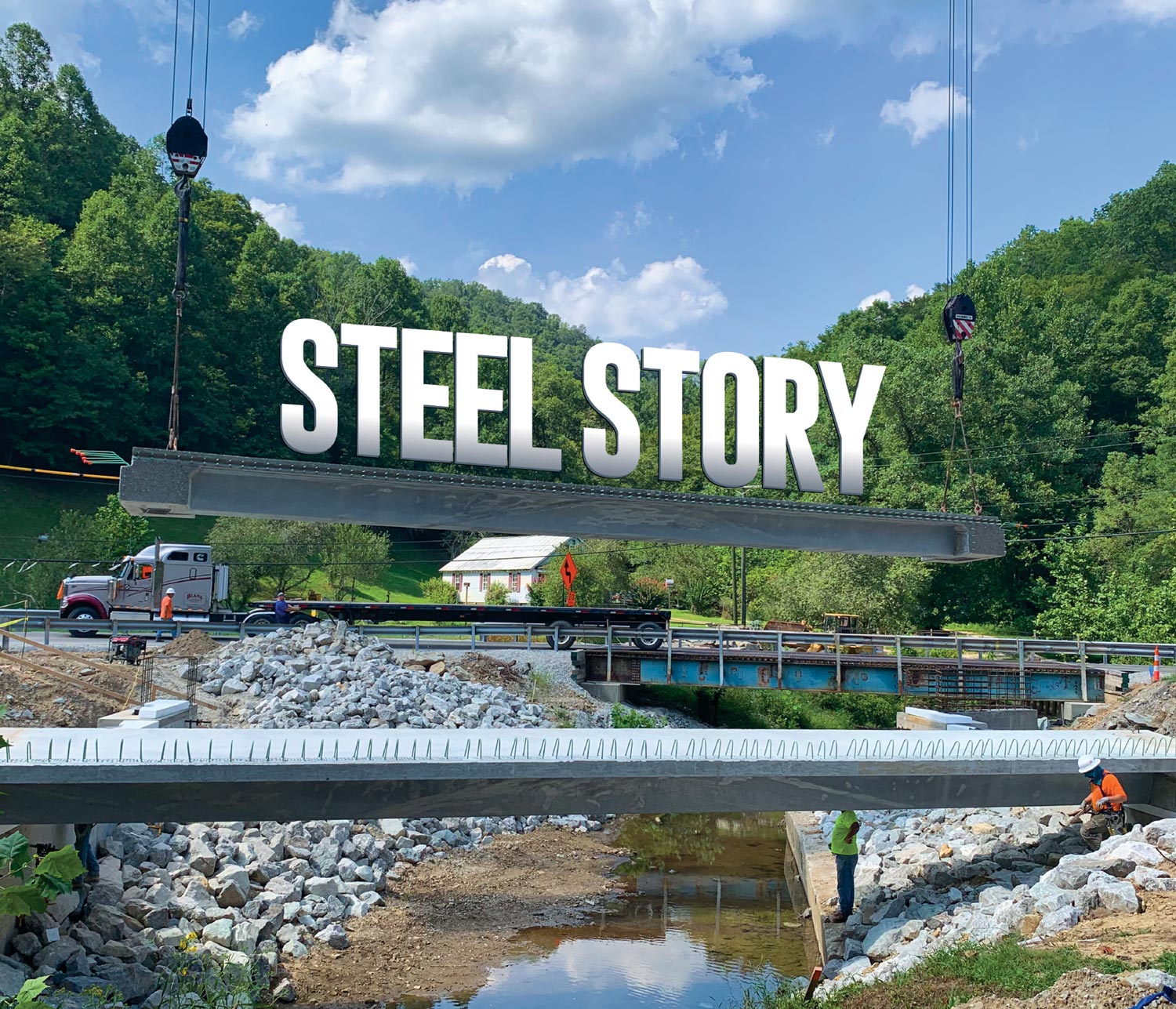

“We need these structures to transport billions of tons in freight from coast to coast,” says Dan Snyder, senior director, business development for the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) and director of the Short Span Steel Bridge Alliance (SSSBA). “Commuters, school buses and truckers make 178 million trips across structurally deficient bridges every day.”

The American Road & Transportation Builders Association estimates costs for the nation’s backlog of bridge repairs at $125 billion. “Repairing and/or replacing these bridges with modern steel designs must be a national priority,” Snyder says.

“There’s been a lot of talk about the infrastructure bill and how it could modernize highways, roads and bridges,” notes Snyder. “We provide education and resources to help guide DOT representatives and county engineers through the process of steel selection for bridge replacement projects,” he says. “Over the last decade, we’ve been actively engaged in developing innovative steel products in five major areas. These areas complement the infrastructure bill, which promotes broader adoption of advanced technologies.

[ B ] The PBTG is fabricated from cold-bent structural steel plate.

[ C ] Using standard plate widths, the PBTG is optimized for maximum structural capacity.

[ D ] The modular units of this weathering steel rolled beam bridge can be shipped on one truck to the bridge site.

[ E ] A concrete or steel deck may be cast-in-place or precast on the girder and installed in hours.

[ B ] The PBTG is fabricated from cold-bent structural steel plate.

[ C ] Using standard plate widths, the PBTG is optimized for maximum structural capacity.

[ D ] The modular units of this weathering steel rolled beam bridge can be shipped on one truck to the bridge site.

[ E ] A concrete or steel deck may be cast-in-place or precast on the girder and installed in hours.

The free web-based tool provides preliminary simple-span and modular designs for steel bridges up to 140 ft. long. It provides bridge owners and designers with customized standard designs for rolled beam, plate girder, press-brake tub girder and buried bridges in less than five minutes. The software provides contacts for design/build projects and access to complimentary support.

Growing labor shortages and the need to contain costs prompted SSSBA to find new ways to address those problems. “Approximately 92 percent of contractors are having trouble finding construction workers,” says Snyder. “We considered how we might develop a system that could reduce labor costs and simplify installation. Prefabricated steel tubs proved an effective solution. It’s lightweight, adaptable and reliable.”

“Cutting, welding and bending operations are performed as part of the prefabrication process off site,” he notes. “As a result, one girder can be installed in as little as 22 minutes. The PBTG system is being used in 11 states. The technology is really taking off.”

Valmont Industries Inc., Valley, Nebraska agrees. Founded in 1946, the fabricator has built its reputation in the renewable energy and agriculture markets. “They saw so much promise in the Press-Brake Tub Girder bridge technology that they put the pieces in place to enter that space,” says Snyder.

One girder can be installed in as little as 22 minutes.

One girder can be installed in as little as 22 minutes.

The plant, which was designed and built specifically for PBTG products, houses a 2,000-ton, 60-ft.-long press brake, an automated plate forming process, automated stud welding, and roll cambering along with a network of qualified coating facilities.

The company developed its own press-brake-formed steel tub girder product, called U-BEAM, which offers standardized shapes and components. Specifying the product is easy, and its production is economical.

“Press-brake-formed steel tub girders eliminate the most costly component of a welded steel I-beam—the web to flange weld—and remove the tension zone fatigue sensitive detail,” says Nelson. “The Valmont U-BEAM can be inspected with simple visual observation of the coating to ensure there is no section loss. If galvanized with a zinc coating, the U-BEAM has a 70-year maintenance-free coating life cycle and an overall service life of 100 years. Both steel and zinc are recyclable, helping to create a more sustainable infrastructure.”

“Today Valmont is one of the largest PBTG fabricators,” Snyder says.

A crew in Buchanan County, Iowa, replaced the Jesup South Bridge with steel, which was designed using the free online tool eSPAN140.

Whitman County, Washington, installed a prefabricated steel bridge using a local crew, saving over $30,000.

“The speed of construction and work off-site has advanced,” Snyder says. “It’s a trend I see moving forward.”

When Mark Storey, director and county engineer for Whitman County Public Works in Washington state, was tasked with replacing two rural bridges, the modular rolled steel girder system caught his attention. “We’ve been building concrete bridges for a number of years, but the material got so expensive that we decided to look around,” he says.

Competitive quotes for the manufacture and delivery of both steel and concrete superstructures revealed that the cost for concrete totaled $82,000, while the modular steel girder system came in at $56,000—an immediate cost savings of 31.7 percent.

“By going with steel, we saved $30,000,” says Storey. “That’s big money for a rural county.”

The Seltice-Warner Bridge’s 69-year-old wood structure was replaced in 2020 by three steel modules with fully assembled girders transported to the work site on one truck. The modules were lifted into place with a front-end loader and attached with simple connections. A corrugated steel deck and rails were installed followed by a gravel surface. The 28-ft.-wide by 35-ft.-long modular steel bridge increased the structure’s hydraulic opening and increased its 100-year-flood clearance.

“A concrete superstructure option would have needed a heavy crane service, which can cost up to $8,000 and can be quite difficult to schedule,” Storey says. “The steel structure took just four people to build in one month, which is pretty amazing.”

By going with steel, we saved $30,000. That’s big money for a rural county.

By going with steel, we saved $30,000. That’s big money for a rural county.

Storey also sourced a modular rolled steel girder system for the county’s Belmont Bridge in 2021. The replacement project eliminated a wood structure in a flood plain. The new prefabricated steel structure was 28 ft. wide by 32 ft. long with an HL-93 loading rating. Whitman County saved $30,000 on the job by specifying steel rather than concrete.

Rural bridges like Seltice-Warner and Belmont are what the industry calls off-system bridges. In the past, states generally had to match federal funding with up to 20 percent state or local funding.

For the first time, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes an incentive for states by setting aside new Bridge Formula Program funds to off-system bridges owned by a county, city, town or other local agency.

Valmont’s U-BEAMs are a fraction of the weight of traditional concrete beams.

There are a total of 281,184 off-system bridges in the United States, according to the National Association of Counties, defined as bridges that are located on a public road that are not part of the federal-aid highway system. This incentive could motivate state and local governments to take up projects that are usually not prioritized and often do not have funding available.

SSSBA is currently developing new steel technology engineered to meet the need for resilient infrastructure that can withstand, adapt and recover from changing conditions. The hybrid steel bridge system reduces life cycle maintenance costs and is projected to last 100 years or more.

“AISI helped to develop the premise for a $400,000 pooled fund study for the hybrid steel bridge system,” says Snyder. “The study is being led by the North Carolina Department of Transportation to research implementation of the new product.”

“Structural steel has a storied history, having been used on iconic structures like the Golden Gate and Brooklyn Bridge,” he says. “The ongoing evolution of steel materials, coatings and fabrication techniques also makes it the right choice for the future.”