raditionalists, Boomers, Gen-Xers, Millennials and Gen Z—catchy labels coined to describe five generations of Americans working shoulder to shoulder. Pew Research reports that millennials represent the largest labor pool but the number of employees age 55 and over is climbing at a projected annual rate of 24.3 percent. The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that Gen-X and Baby Boom workers will number 13 million by 2024 with millennials making up the majority by 2026.

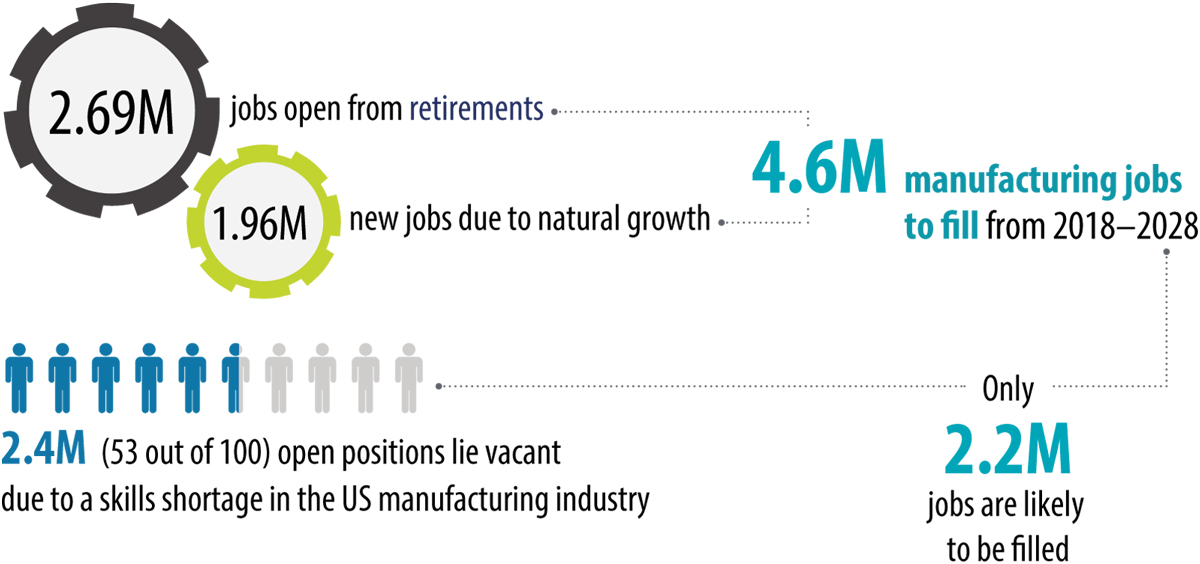

A skills gap study published in 2018, the fourth such report prepared by Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute, reveals troubling statistics. It states that the industry may have up to 2.4 million jobs to fill between now and 2028. This deficit puts U.S. $2.5 trillion in economic output at risk over the next decade.

As Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 continue to modernize manufacturing with digital factories and smart machines, companies and educators want to know how to close the gap with qualified workers. Sarah Boisvert, author of a 2018 insider’s guide to making positive changes to manufacturing and training, conceives of a new collar workforce that can “run automation and software, design in CAD, program sensors, maintain robots, repair 3D printers and collect and analyze data.”

In a grassroots movement that promises to help build a talent pipeline, Cairo Elementary, Westside High School, Vaughn College, Norton Abrasives/Saint-Gobain and AIMS Metrology have unique answers to a perplexing question.

“Our research showed that 65 percent of children today will end up in a career that doesn’t exist yet,” she says. “There is also a scarcity of women in the STEM workforce. According to statistics, only 15 to 25 percent of these positions are filled by women.”

One of the school’s missions “is to lay a foundation for 21st century learning,” says Shappell. “To do that, our district has an initiative to provide authentic learning experiences that foster collaboration, communication, critical thinking, innovation and initiative. Transforming our [library] was a big push behind building a better graduate.”

**Retirement age of 66

Sources: BLS Data, OEM (Oxford Economics Model), Deloitte and Manufacturing Institute skills research initiative.

The school district’s maintenance and electrical staff installed the machine. Local manufacturers such as Perfection Tool, Air Hydro Power and Sunspring America Inc. also provided support, as well as Dallas-based Push Corp. Inc. “When we got the robot, we thought, What do we do with it?” Brooke Shappell recalls. “Mike dedicated many hours to setup and to working with the kids to code and operate the robot.”

Mike Shappell, over a 40-year career, has witnessed how difficult it is to find people who can code and maintain robots. “Over the last 10 to 15 years, we haven’t been training individuals in these skill sets unless they were going to work for a robotic or CNC supplier.

Cairo Elementary launched a Robotics Club in October 2019. The members, four boys and four girls, meet weekly. Guidance on how to protect and prepare the robot, simple programming and basic movements culminated in two-member teams demonstrating complex maneuvers in December for parents and the community. “You can see their minds problem solving in real time,” says Shappell. “And they do a good job. Of course, this generation isn’t intimidated about pushing buttons.”

“I’m the dreamer,” says Bombac, who took over as lead weld instructor in 2017. “The idea took root five years ago when I went to my department head asking for more space.”

He credits Terry Hanna, Westside Community Schools Foundation’s development director, with making the vision a reality. “How many schools have a foundation person going out all day long asking for things?” he says.

The project attracted 40-plus donors, including some of Nebraska’s key corporations and the state’s Department of Labor. The foundation partnered with area companies to help craft a curriculum. “They had a lot to contribute in terms of identifying career paths and giving us feedback on the types of skills they were looking for and skills they no longer needed.”

The lab contains benchtop precision machine tools, lathes and mills along with 20 welding stations. “The entire lab is portable—almost like a Transformer,” Bombac says. “If we are working on a large project, we can fold up the desks and move them to create more space.”

ONLY 15 TO 25 PERCENT OF STEM POSITIONS ARE FILLED BY WOMEN

Student feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. “The kids tell us this is the greatest time in their lives,” says Hanna. “They are proud to say they are part of this program. You can see their energy and their excitement about learning. I recently drove through an industrial area with posted signs that said, ‘Welders and Steam Fitters Needed.’ With a starting salary of $40 an hour, a 401K and health insurance, if a kid isn’t interested in pursuing a traditional path, why wouldn’t they think about a job like this? It could even be a path to becoming a business owner.”

In 2019, AIMS’ educational discount on its Revolution series mobile, 5-axis HB CMM with a Renishaw PH20 probe head, attracted the attention of Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology. Founded in 1932, the Queens, New York, college has degree programs accredited by ABET, a specialized accrediting agency recognized by the U.S. Secretary of Education and by the Commission on Higher Education. Courses are crafted around input from Vaughn’s advisory board, which is made up of local manufacturers.

65 percent of children today will end up in a career that doesn’t exist yet

The course, slated for a 2020 launch, will take place in a job shop environment outfitted with CNC machine tools, go/no-go gauges and the HB. Students will read blueprints, cut real parts and learn to measure them with both the gauges and the CMM. “You never fully appreciate what you have learned until you do it on the job,” says Jesus.

The course mimics job requirements for setup personnel, operators, programmers and quality inspectors. Students will get a feel for each position. Lab Assistant Rachid Nafaa has 39 years of machine shop experience and is a Vaughn graduate. “If you know how to read a print, you can cut a part, write a program and inspect it,” he says. “The more machines you know how to operate, the more money you make. If you know how to program and operate a CMM, companies will pursue you.”

Demand for a 100 percent acceptance rate on parts and the ability to measure complex features in a smart factory environment creates greater interest in CMM equipment like the HB and in programmers and operators who know how to use them.

The growth of additive manufacturing also has Jesus and Nafaa talking about expanding the course to include a metal 3D printer.

“We see more customers printing parts and then using the CMM to inspect them,” notes Gearding. “Additive manufacturing puts a supplier ahead of the game because a programmer can print a part and check it right away instead of waiting for a program to be debugged before starting a production run.”

Building and managing a pipeline of blue, white and new collar personnel is part science, part art. Focusing on statistics alone can lead one to see manufacturing’s glass as half empty. Institutions like Vaughn, Cairo Elementary and Westside High School and equipment suppliers like Norton Abrasives/Saint-Gobain and AIMS Metrology are helping to fill the glass by heeding employers and shaping a multi-faceted workforce.